In truth, Lefty had a lot more kids.

Well over 1,000.

Some of them went on to become Olympians, as did LaVonna, who competed in the Seoul Games in 1988 and four years later in Barcelona won a silver medal in the 100-meter hurdles.

He had 60 kids who were national youth track and field champions. Several won state high school titles and nearly 300 got college athletic scholarships, with many of them going on to become NCAA champions and All Americans.

Hundreds and hundreds of them ended up as part of the fabric of this community and so many others across the nation. They are our teachers and preachers, coaches, doctors, engineers, factory workers, husbands, wives, grandparents and so much more.

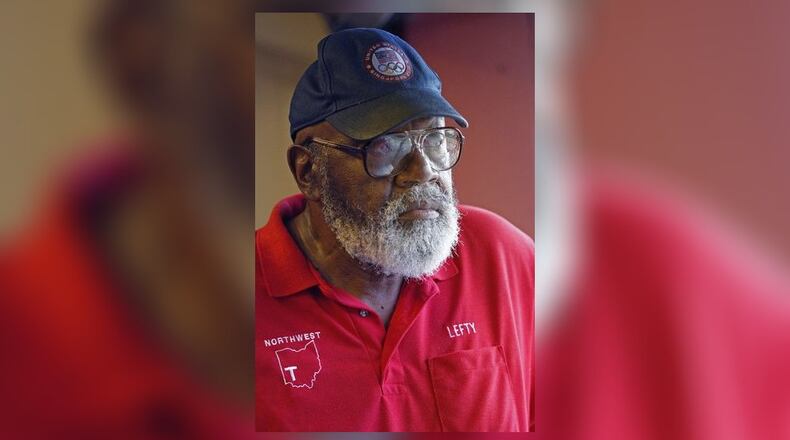

Martin died last Monday. He was 84 and a beloved figure in the sports world.

While a memorial service will be announced in the future, his passing is now sending ripples of reflection through the community because of all those “kids” he had and the way he impacted their lives.

He and Brenda started the Trotwood-based Northwest Track Club in 1978. Early on, Dave West, the New York Jets defensive back, helped out, but the Martins were the identity and the backbone of the effort for decades.

Initially, they wanted to provide an outlet for their two oldest children — LaVonna and Duane — who showed promise in track. Other kids soon flocked to them the way the swallows were drawn to Capistrano.

Credit: NONE

Credit: NONE

Lefty once told me about a girl in the early 1980s — Mary Hawkins — who used to ride the Greyhound bus back and forth two times a week from Columbus to Northwest Track Club practices. She would go on to be a standout at East High and later ran for Panama in the Olympics.

Tonja Buford-Bailey, another Northwest Track Club product, starred at Meadowdale High and the University of Illinois — where she was a 10-time All American and the NCAA 400-meter hurdles champ — and then ran in three Olympics, winning a bronze medal in the 400-meter hurdles at the 1996 Atlanta Games.

No one though was quite the tour de force that LaVonna Martin-Floreal (she’s now married to Texas track coach and former Canadian Olympian Edrick Floreal) was.

She single-handedly led Trotwood Madison High School to state titles in 1983 and 1984 by scoring all her team’s points. She was a 14-time All American at Tennessee and then came the Olympic efforts.

Thanks, in part, to her, the Northwest Track Club became one of the best-known developmental programs in the nation.

But once again, in truth, it was about far more than track with Lefty and Brenda.

“We try to stress more than just the actual sports,” Brenda once told me. “We try to make the club about the most important things, too: integrity, doing things the right way, and we really stress getting an education. We want our kids to be able to get scholarships and go to college.”

For decades Lefty was fully committed to that effort.

“That was the baby he created,” LaVonna told me the other day from her home in Texas. “My parents treated the Northwest track kids as their own children.”

That’s why in 2015, Bing Davis, the internationally-acclaimed artist, educator and community activist from Dayton, made the perfect choice for the prestigious Dayton Skyscraper art show that occurs here each year. He chose Lefty Martin as the subject of his offering.

The Skyscraper awards honor local African American men and women who stand tall in the community as role models and leaders.

“We try to get broader role models for young people and young men in general to show them individuals who are excelling beyond some of the areas they focus on, like the NBA, the NFL and hip-hop. And Lefty is really the epitome of our efforts,” Davis said.

“Even though he was once the big man on campus himself, what he is doing now is even greater than all his records in Pittsburgh and at Central State.

“That’s why I named the entry Beyond the Finish Line.

“He is an athlete who has stayed active in the community. To work with all these young people around here and have them break national youth records and then better participate for their high schools and go on to college and some even go on to the Olympics to me that is what being a Skyscraper is all about.”

Lefty, in his typical gruff, focus-on-somebody else manner, scoffed when I told him what Bing had said:

“I don’t know about all that. I’m not in it for that. This is just my passion, something I love doing. I see so many talented athletes come along, and I just want them to improve from one week to the next.

“I want them to have success, and I want to be there to see it.”

And he saw a lot of it, not just at the Northwest Track Club, but when he launched the University of Dayton track program in the mid-1990s and ran it for seven years. He also coached the Wilberforce University team.

He was a race official for numerous college conferences, including the SEC, Big Ten, ACC, Atlantic Sun, Big South and MEAC.

He was a referee at various USA Track and Field and Junior Olympic events and became a site inspector at meets around the country. Over the years, he coached hurdlers in Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, Scotland, Singapore and Cuba.

In 1983, as the meet director of Youth Athletics National Championships, he brought the event and its 4,000 athletes to Dayton, where, for the first time, boys and girls competed in the same meet.

As Brenda once explained:

“That man just loves track. He goes to bed talking about track. He wakes up talking about track. He talks about track during the day. All day, Every day.”

When I told him what Brenda had said, he shook his head: “No, I like fishing, too.”

Central State hall of famer

“Like most black families my grandparents came through the Great Migration,” LaVonna said. “They came up from South Carolina to Pittsburgh and, like all the families, they wanted their child to have it better than they did.”

Lefty’s dad was a waiter at the restaurant in Kaufmann’s department store in Pittsburgh. His mom worked as a domestic in private homes.

He was their only child, and he soon starred in track at South Hills High School. One headline in a local paper read: “Pittsburgh’s Fastest Boy.”

A cousin of his was going to Central State and she showed some of Lefty’s clippings to the Marauders’ legendary coach, Gaston “Country” Lewis, who soon offered him a scholarship.

Once he got to the Wilberforce campus, Lefty made the most of the opportunity he’d been given.

He was the first CSU athlete to run the 100-yard dash in under 10 seconds, clocking a 9.8 at a school meet, and 9.5 at an AAU event. He also was the stalwart on two of the Marauders’ formidable relay teams.

While at CSU he was elected the student intramural director and ran competitions in five sports. A double major (music, as well as health and recreation), he also played the tuba.

He is now enshrined in the CSU Hall of Fame.

After graduation he got a job at the Dayton Boys and Girls Club. That’s where he met Brenda Young, then a University of Dayton student, who had a summer job working for the City of Dayton recreation department.

She once told me they unknowingly had been in each other’s presence before that:

“When Lefty’s mother died, we were cleaning out the attic and I came across a program from an AAU meet at Welcome Stadium. I said, ‘Oh my God, Lefty, look at this! There’s your name and here’s mine.’ He was running in college, and I was still in high school then.”

Lefty eventually began a job at the Dayton Veteran Affairs Medical Center where for 28 years he served as the Chief of Recreation Therapy.

LaVonna said her dad was a good provider and she and her sister and brothers got all they needed from him — except time.

When you are so committed to track as he was, you’re often away from home.

She said her mom was the glue of the family, while also doing all the paperwork and cultivating many of the personal relationships of the track club.

She said her parent’s long marriage can be attributed, in part, to them having the same interest — the track club.

I once asked Brenda and Lefty the secret of their long marriage.

“I pray a lot,” Brenda said.

With deadpan delivery, Lefty said: “I stay out of her way.”

Lasting impact

LaVonna said her dad’s success stemmed, in part, because he was stubborn. He had a way he did things, and he wouldn’t waver. Mostly, that was a good trait.

He did believe in routine.

He used to fish on Fridays. Sometimes at Indian Lake, other times at St. Marys, or Lakengren, south of Eaton. On occasion he went to Lake Erie.

He passed his interest in music on to his kids, too,

“We each had to learn to play some kind of instrument,” LaVonna said with a chuckle as she remembered her early days at the piano.

“And we always had to watch the Macy’s Parade. Just to see the bands. Even now, I’d call him every year before the parade to let him know I’d be watching. That’s a tradition I’ll try to keep going with my kids (E.J. and Mimi.)”

On his right hand, Lefty wore a Pittsburgh Steelers Super Bowl ring that sparkled with six stones representing six NFL titles.

He held tight to his roots and that included the work ethic he saw his parents exhibit. He believed his track kids could excel if they put in the work and mostly that did happen.

There were a few casualties. One star went to prison. One girl was killed in a robbery. A guy in the service was hit by a train.

When he talked about them once, a noticeable sadness came over him.

“You just wish you could help them all succeed,” he said in voice that was nearly a whisper.

He helped so many of them though and that effort struck a real chord with Davis, who has done the same for others in his life.

Back when he honored Lefty, he stressed how Martin was doing something in this community “that is very special, very unusual.

“Long after his own career was over, long after he had run all those races and won all those trophies, he found a way to continue to contribute to the quality of life in the Miami Valley. Over the years he’s touched the lives of so many young people here. To my eyes, that what makes him a Dayton Skyscraper.”

And now, even though Lefty Martin is gone, his towering presence still rises up all around us.

You can see it in all his kids.

They are our teachers and preachers, coaches, doctors, engineers, factory workers, husbands, wives, grandparents and so much more.

About the Author